Click here to access all info on Bridgespan

Making Sense of Uncertainty: Nonprofit Scenario Planning in the COVID-19 Pandemic

by Lindsey Waldron, Robert Searle, Alexandra Jaskula-Ranga

Summary

Nonprofits can’t be sure how the pandemic will affect society, the economy, or their own field six months or a year from now. But they can navigate the uncertainty with greater confidence by building scenario plans that can help them continue to pursue their missions.

Nonprofit leaders have taken heroic steps to continue their organizations’ important work as COVID-19 swept across the world. They’ve been able to make sure their cash is under control, provide emergency relief, and keep staff and constituents safe—all while staying on mission under extraordinary stress. Yet they still can’t be sure how the pandemic will affect society, the economy, or their own field six months or a year from now.

How can you make smart decisions when faced with such vast uncertainty over time? “Don’t let the daily issues bleed into the longer-term planning, and vice versa,” suggested one nonprofit leader we talked to during the pandemic. Responding to the short term has been paramount but preparing for the longer term is no less pressing. That’s where scenario planning comes into play.

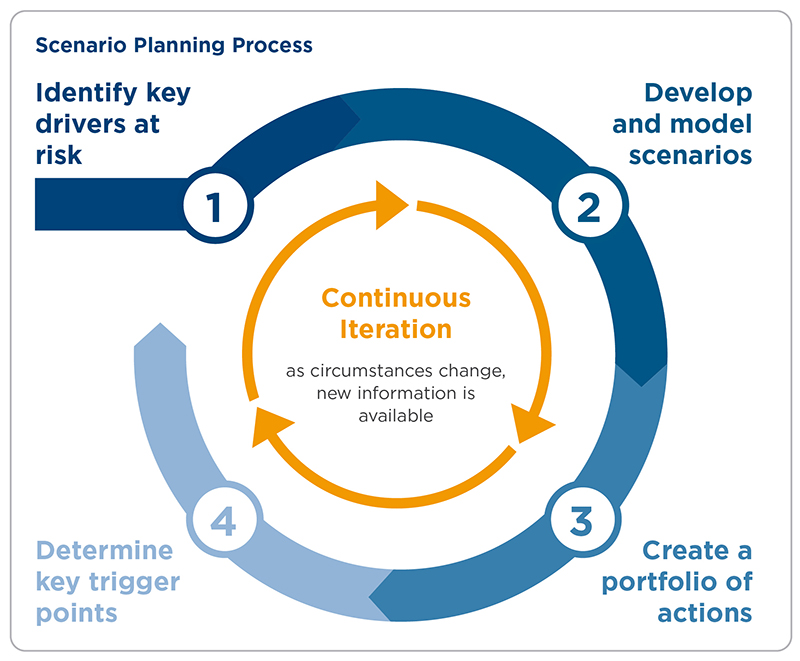

Scenario planning helps organization leaders navigate uncertainty while providing structure around making key strategic decisions. This article, and the accompanying tool, can support you and your leadership team through a scenario planning process that could help preserve your organization’s ability to pursue its goals for impact. We carefully adapted Bain & Company’s coronavirus scenario planning guidance and strategy in uncertainty methodology, and worked with a number of nonprofit leaders to put this approach into practice.1

Use the Scenario Planning Toolkit

First comes some homework. Decision making under uncertainty starts with clarity on guiding principles for your organization. (See “A Compass for the Crisis: Nonprofit Decision Making in the COVID-19 Pandemic.”) The principles reflect your organization’s unique mission, values, and circumstances, and articulate how you will approach tough tradeoffs balancing your mission, finances, staff, equity, and other considerations. They’ll also help you communicate the rationale behind tough decisions to key stakeholders. If you haven’t already aligned on guiding principles in your initial crisis response, you’ll want do to so before embarking on the four-step scenario planning process outlined below.

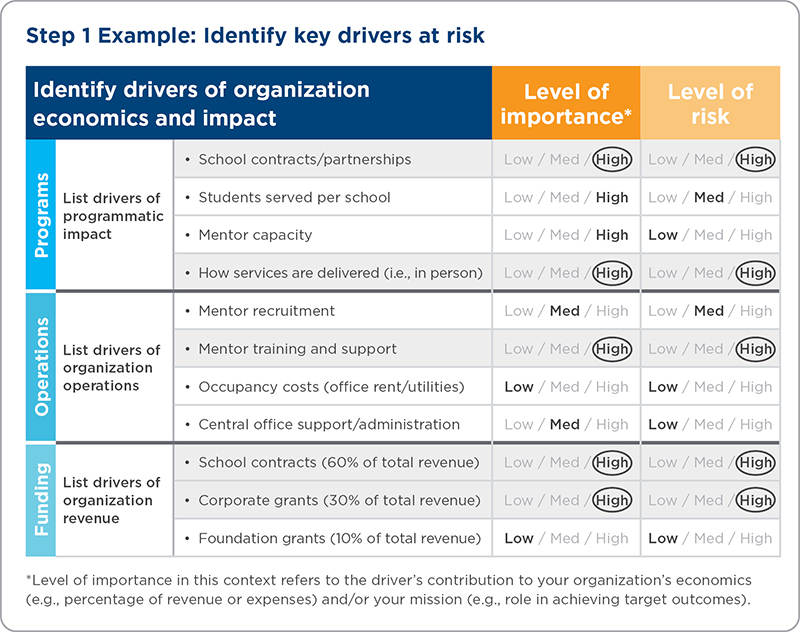

Step 1. Identify key drivers at risk

With guiding principles in hand, you’ll start scenario planning by identifying the drivers of your organization’s economics and impact. These are the elements or variables that animate your day, or keep you up at night, typically in three categories—programs, operations, and funding. Think client demand (e.g., student enrollment or patient volume), staff capacity, contract revenue, foundation grants, or others.

You may have a long list of drivers, so you’ll want to prioritize them by level of importance and level of risk. In evaluating levels of risk, consider three questions:

- What is the nature of the risk associated with the driver?

- What is the likelihood that the risk plays itself out?

- If the risk played out, how much of an impact would it have?

A risk with a high likelihood and high impact of course indicates a high level of risk. But so much is uncertain, so you’ll have to rely on a combination of external sources (such as guidance from public health experts or economic data) and good judgement to make best guess assessments across all drivers and their risks.

The best way to describe these steps is through an example.2 Let’s look at a mentoring organization that works in public schools. The nonprofit identified a number of drivers of economics and impact—11 in all. These included the number of students served, the recruitment of mentors, and school contracts.

It then needed to decide which of the drivers mattered most. To use all 11 in the next steps of the scenario planning process would be too complicated; with scenario planning, clarity is more important than complexity. So the organization prioritized the five drivers it judged to have both high importance and high levels of risk associated with them. These became its key drivers.

For example, the organization relies on delivering its mentoring services in person. That model is of high importance to the organization’s impact model—and very much high risk because of the likelihood that social distancing practices become part of the norm. Notice, as well, that other drivers, like mentor capacity, are high importance but low risk and thus less critical to address in scenario planning. In this example, the organization realized that volunteer mentor capacity might actually increase in a down economy and therefore the risk of mentor capacity drying up is low.

For simplicity’s sake, we’ve used an example with one main program. Organizations with multiple programs should begin by focusing on the programs that are central to their missions and economics.

Let’s quickly consider two other examples where the organizations had to think about other kinds of drivers. A multisite nonprofit health center conducting this exercise decided to focus on three key drivers: patient volume, healthcare revenue, and patient mix. Like most health organizations, it’s heavily dependent on third-party payers (whether public or private) for its revenue. The reason it also chose to focus on patient mix is because serving people of color and lower-income communities with less access to health services is key to its mission. If it chose only patient volume and healthcare revenue as key drivers, the planning process might end up focusing almost exclusively on economics at the expense of equity and mission—a particular problem when its patients of color may be disproportionately affected by COVID-19. For mission-driven organizations, the most effective scenario planning process will consider both economics and impact.

Another example is a nonprofit cultural institution that relies on admissions for most of its revenue, and has high fixed costs to maintain its facility and cultural assets. Communities often have many such institutions—museums, zoos, historic houses, or other sites. In a time of social distancing, this particular institution selected admissions and special events as being both of high importance and at high risk, and focused on these two during its scenario planning process. While grant revenue and research are also significant elements of its operation, those drivers faced relatively low levels of risk and were therefore less critical to address in scenario planning.

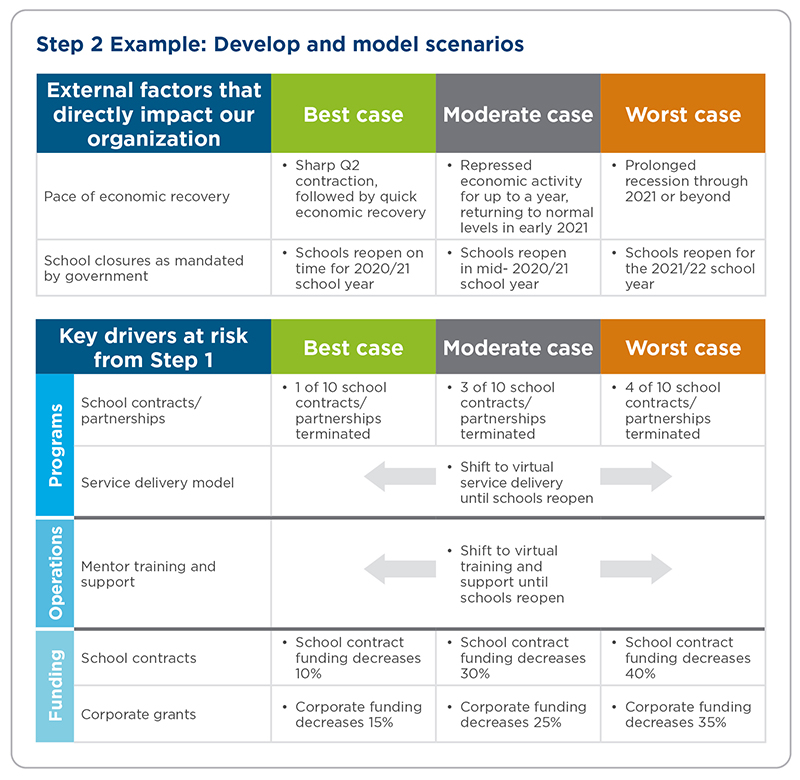

Step 2. Develop and model scenarios

Develop best-, moderate-, and worst-case scenarios that reflect the full spectrum of possible outcomes for your organization. Your scenarios should anchor on the key drivers—the ones that are high importance and high risk—that you prioritized in Step 1. As you assessed the level of risk for each, you probably thought about external factors—for example, government social distancing rules, the pace of economic recovery, unemployment rates, school closures, and public attitudes about engaging in certain kinds of activities (like volunteering, seeking health services, or going to a cultural institution)—that are beyond your control. Now, it’s time to build scenarios around those external factors, focusing on how the few that are most relevant to your organization play out in best, moderate, and worst cases.

Recall that for the mentoring organization, its five key drivers were: whether schools opt in or out of the mentoring program, how it delivers services to students, whether social distancing rules will make it harder to train and support mentors, and the potential for cuts in school contracts and corporate funding. For this step, the organization chose to focus on scenarios that depend on when, and whether, schools reopen. While many other external factors are important, this is a critical on/off switch for the organization. It affects how the organization delivers services to students and how it works with mentors. Of course, the organization is also keenly aware that its funding streams are dependent on the economic recovery, another external factor in its scenario analysis.

For each scenario, in the chart below, the mentoring organization estimated how its key drivers may be affected—focusing specifically on the impact on the organization’s revenue streams. Understanding the potential financial impact of each scenario will help tee up an important conversation in Step 3 around options for action.

For the nonprofit health center, the most important external factors it decided to focus on—given the drivers of patient volume, healthcare revenue, and patient mix—were: the status of the shelter-in-place mandate (which affects whether patients can visit in person), unemployment rate (which significantly affects health insurance status and therefore reimbursement rates), and the continued viability of telehealth in terms of both patient acceptance and insurance reimbursement rates. It developed best-, moderate-, and worst-case scenarios for these external factors using the best available data—and mapped their potential impact on patient volume, healthcare revenue, and patient mix. Because the health center is working with three main external factors, it could have gotten complicated. But it kept things simple by grouping external factors to come up with overall best-, moderate-, and worst-case scenarios for which it could then plan.

The cultural institution also chose to focus on three external factors: when shelter-in-place restrictions will be lifted for its sector (which could conceivably come later than for other sectors of the economy), capacity constraints as a result of social distancing rules, and how willing the public will be to visit its site. Of course for another type of cultural institution—one much more dependent on grants or private donations than on admissions revenue—the key external factors might be different (perhaps more focused on economic conditions than COVID-19 control regulations or the public’s willingness to visit).

Anchor your financial modeling in a time horizon that is relevant for your organization and budget cycle (e.g., six months). Some will find it helpful to consider multiple time horizons. But whatever your time horizon, remember two things:

- Don’t aim for precision. The goal is to work with your management team to understand possible outcomes and plan accordingly.

- Don’t underestimate the worst case. Your worst-case scenario should reflect possibilities that could have serious consequences for the organization.

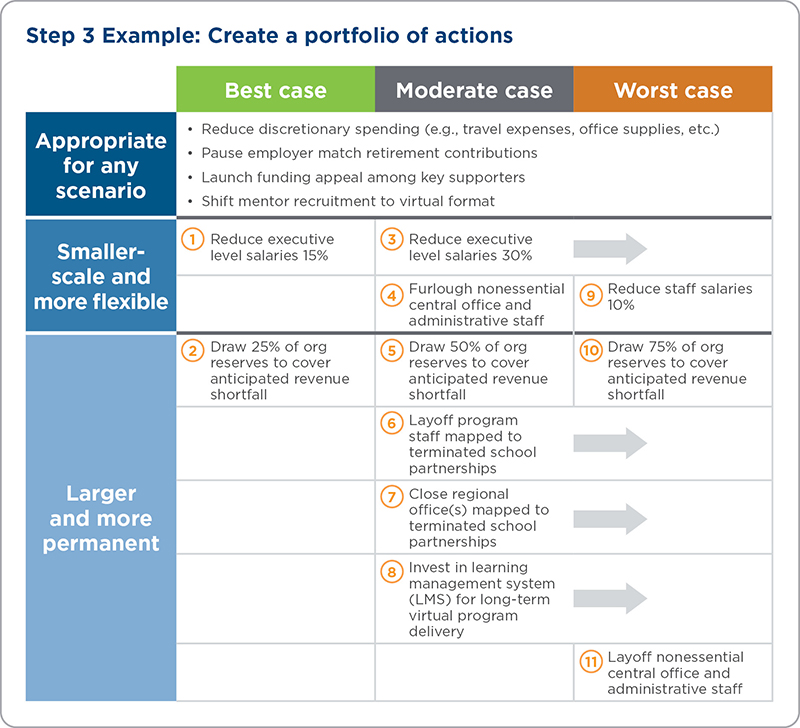

Step 3. Create a portfolio of actions

Next, you want to develop a set of actions that would allow you to effectively manage against each scenario—or across all of them.

Actions typically fall into one of three main categories:

- Appropriate for any scenario: These actions are likely to benefit the organization’s ability to deliver impact and support its financial health under any future scenario.

- Smaller-scale and more flexible: These actions can be executed quickly, and potentially reversed, if needed.

- Larger and more permanent: These actions involve large-scale investments or cost reduction measures and may be harder to reverse.

The actions will likely have some economic cost or benefit. Quantify the potential costs incurred or savings achieved for each action individually, over whatever time horizon the action would be implemented. Then, calculate the total estimated costs incurred or savings achieved by each set of actions for your best-, moderate-, and worst-case scenarios. And keep your guiding principles top of mind; they will serve as an invaluable compass to ensure your actions balance these financial costs and benefits with your mission, your staff, equity, and the other considerations that your leadership team agreed upon.

Here is how the mentoring organization approached Step 3. It focused on several actions it could take—drawing from reserves, reducing staff salaries, temporarily or permanently laying off staff, and so forth—and mapped them against its three scenarios. Sometimes a scenario required a new action—like closing an office—and sometimes it required more of what they were already doing even in the best scenario—drawing on reserves, cutting salaries.

Depending on the scenario, the multisite health center identified several potential actions, including: reducing or expanding hours of operation, changing the location of health center sites, temporarily or permanently laying off staff, and hiring additional staff with the capability to perform the highest demand services. One of its guiding principles is to ensure health equity by focusing its services on those populations most in need of critical care. Thus, the center is also considering how potential shifts in its patient mix, one of the key drivers it identified in Step 1, will motivate action. For example, it may increase telehealth offerings to reach a more diverse patient base or open new sites in low-income communities where demand for its services is increasing.

Likewise, the cultural institution specified a range of possible actions for each scenario, including: developing virtual programming, securing philanthropic support to accommodate a temporary shortfall in admissions, reducing staff, creating remote guided tours by videoconference, and changing the ways in which people move through the site to ensure social distancing.

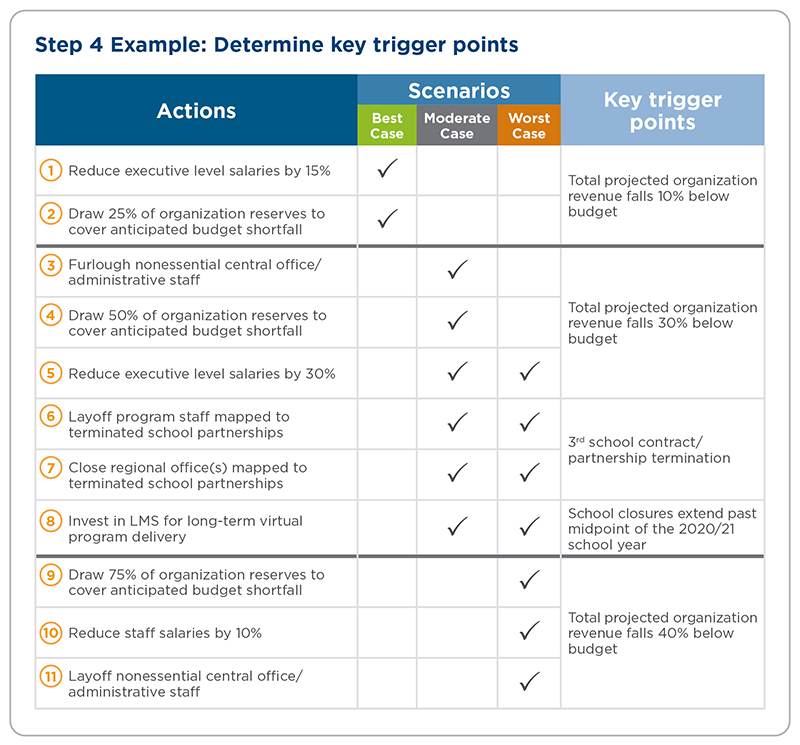

Step 4. Determine key trigger points

So far in this process, you have prioritized key drivers of your organization’s economics and impact facing high levels of risk; developed best-, moderate-, and worst-case scenarios; and crafted a portfolio of actions appropriate for each scenario. This last step involves identifying clear trigger points that will prompt decision making and action on the part of your leadership team. At what point would you have to let which staff go? When should you press pause on certain employee benefits? What will prompt you to shut down a program delivery site or open a new one where needs are increasing? These are tough questions requiring tough answers, but these trigger points—whether signaled by internal metrics or external events—can serve as guardrails for you and your leadership team through the crisis and its aftermath. They will also help speed up decision making down the road. You may want several trigger points, or one that is the best gauge for multiple actions.

Here, the mentoring organization lays out its potential actions by scenario, with a trigger point for each. The trigger points it identified take different forms—specific levels of revenue reduction, the opening or closing of the school system, and the termination of partnerships with particular schools.

The multisite health center has selected a lifting of shelter-in-place rules, a loss of a specific percentage of healthcare revenue, and a decrease of a specific percentage in patient volume as its trigger points for action. The cultural institution chose the lifting of shelter-in-place rules and a percentage drop in admissions revenue.

* * * * * *

Scenario planning in the pandemic—where so much remains unknown—is both challenging and necessary for nonprofits, as they navigate these unprecedented circumstances and work to preserve their ability to deliver impact. Taken together, these four steps provide a way to think about the different scenarios you might need to adapt to in the coming months and how to think through the difficult choices you may need to make.

A scenario plan can provide a powerful structure for coping with risk and uncertainty, but it is not the kind of structure that ought to be set in stone. Rather, the best scenario plan is a living document—continually revised as new information flows in. If your best assumptions turn out to be wrong, make new ones and course correct. In this fast-changing environment, planning needs to be iterative—taking into account important new information as it becomes available. After all, you are not trying to predict the future, you are preparing a response for whatever future arrives so that you can focus on pursuing your mission.

Lindsey Waldron is a manager in the Boston office. Robert Searle is a partner in Bridgespan’s Leadership practice and Alexandra Jaskula-Ranga is a consultant in the Boston office.

The authors would like to thank Bradley Seeman and Larry Yu for their support in writing this article. They also thank Mara Seibert for her work on the design for this article and its accompanying tool.

Notes

1. We’ve worked extensively with this approach to scenario planning, and we acknowledge there are other ways of going about it. For example, the Nonprofit Finance Fund has assembled a collection of COVID-19 tools and resources for nonprofits, including scenario planning tools. Fiscal Management Associates offers a collection of tools to support nonprofits in managing their finances during this period of uncertainty, including a revenue scenario planning tool.

2. All three examples in this article are based on actual US-based nonprofits we’ve talked to about scenario planning during this crisis, but we have taken liberties with the details to preserve confidentiality and simplify the example. All three involve some form of direct service, but the same steps apply to an advocacy or policy organization, or an intermediary.