Click here to read on Stanford Social Innovation Review

By Daniel Parks

Many examples testify to the fact that when a philanthropic program doesn’t include beneficiaries in its decision-making processes—nonparticipation—it exposes itself to risks that reduce its likelihood of success. These risks include functional risks related to program efficiency and effectiveness, and ethical risks related to the morality of the program and its effects.

The root of nonparticipation’s functional risks is most often the use of bad information, which may come from an inaccurate or incomplete understanding of the program’s intended beneficiaries and the challenges they face. The likely consequences are inefficiency at best or counterproductivity at worst. The root of most ethical risks is the undemocratic exclusion of intended beneficiaries from matters that directly affect their lives. The likely consequence of nonparticipation’s ethical risks is that the philanthropic program amounts to an immoral enterprise, undemocratically doing harm to its intended beneficiaries.

Consider the infamous example of PlayPumps International, an NGO that in the mid-2000s connected children’s merry-go-rounds to water pumps throughout rural Africa, with the aim of providing clean water to remote communities. In due time, a UNICEF report made it clear that access to clean water for these remote communities was contingent on an unintended form of community labor rather than play; that PlayPumps were replacing existing handpumps without community consultation; and that some pumps were reportedly installed on unsuitable sites, fell quickly into disrepair, and often failed to receive promised maintenance.

The program’s lack of beneficiary participation is supported by the fact that the supposed beneficiaries at 63 percent of PlayPump sites visited in Zambia during the creation of the UNICEF report indicated that the program did not adequately consult them or present an alternative to the PlayPump. Moreover, these supposed beneficiaries preferred the previously existing handpumps the program removed to install the PlayPumps. As a most basic criticism, PlayPumps International’s lack of information about beneficiaries’ needs and preferences resulted in wasteful implementation. The organization’s exclusion of beneficiaries from decision-making in their own communities resulted in the program undemocratically installing devices that some women felt embarrassed to operate and that sometimes caused people to vomit after spinning.

These points demonstrate how a program and its intended beneficiaries can suffer from the functional and ethical risks of nonparticipation. It is therefore worth asking: How could those of us working in philanthropy have foreseen these outcomes? Looking at other philanthropic failures, how could aid organizations have foreseen that supplying communities in Sub-Saharan Africa with mosquito nets might unintentionally endanger fish populations and poison food and waterways? Or, how could the Red Cross have known that its attempt to provide permanent housing and infrastructure to tens of thousands of people in poverty-stricken Haitian neighborhoods would produce only six permanent homes?

The answer to all of these questions is that most philanthropic organizations could not have foreseen these failures—that is, unless they included their intended beneficiaries in program development and operation.

It is unsettling to witness well-meaning attempts to do good fail and garner criticism with a moral undertone—though such is only natural to an industry like philanthropy, which prides itself on being about moral enterprise. And it is worth recognizing that participation is not a panacea for all of philanthropy’s problems. Even meaningfully participatory philanthropic programs can make mistakes, and funding constraints are always a concern. But the truth in these reflections ought not to make us stubborn. An honest assessment of philanthropy’s shortcomings tells us that we must do much more to give intended beneficiaries more power in program decision-making processes. Yes, meaningful participation is hard. But it is certainly worthwhile given the profound risks nonparticipation poses.

Of course, many funders and administrators tacitly accept that meaningful participation is an important factor in sustainable philanthropic success. But we don’t always know how to go about having a conversation that honestly examines and shapes a program’s priorities. How can we understand a program’s exposure to the risks of nonparticipation? How can we identify problems and opportunities for change? How can we use that knowledge as an impetus to action? A framework can help.

Measuring the Risks of Nonparticipation

Participation in philanthropic programs is a well-covered subject, and various tools—including Arnstein’s Ladder, the Global Fund for Community Foundations’ Community-Led Assessment Tool, and the Movement for Community-Led Development’s Community-Led Development Tool—exist to help philanthropic organizations consider the participation process with nuance. However, while this existing work is invaluable, some of it isn’t yet adapted for philanthropy and can be difficult to apply to the practical purpose of measuring nonparticipation as a risk.

To help address these limitations, the following framework aims to bring contextual factors relevant to participation to bear directly and more completely on conversations about participation, program processes, and risks. It’s intended as a practical tool for understanding the type and scale of risks to which a philanthropic program is exposed, and factors that contribute to participation-related problems and opportunities.

That said, it’s important to note that its benefit—in attempting to present a matter as complex as participation in a digestible and actionable format—is also one of its weaknesses. Most basically, it can help start a necessary conversation, but those interested in making their programs participatory should be prepared to engage the process further, with the due respect and depth it requires.

I. Assessing Functional and Ethical Risks

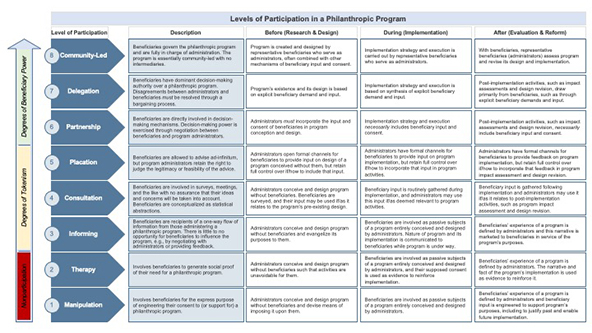

There are three main parts to the framework. The first is adapted from Arnstein’s Ladder, and measures how exposed a philanthropic program is to the functional and ethical risks of nonparticipation by rating participation levels at different stages of its operation.

There are eight levels of participation. From least participatory to most, they include:

- Manipulation: The program involves beneficiaries for the express purpose of engineering their consent to (or support for) a philanthropic program.

- Therapy: The program involves beneficiaries to generate social proof of their need for a philanthropic program.

- Informing: The program has a one-way flow of information from those administering it to the beneficiaries. There is little to no opportunity for beneficiaries to influence the program, such as by negotiating with administrators or providing feedback.

- Consultation: The program involves beneficiaries in surveys and meetings, but provides no assurance that their ideas and concerns will be taken into account. The program conceptualizes beneficiaries as statistical abstractions.

- Placation: The program allows beneficiaries to advise ad-infinitum, but administrators retain the right to judge the legitimacy or feasibility of the advice.

- Partnership: The program directly involves beneficiaries in decision-making mechanisms, and exercises decision-making power through negotiation between beneficiaries and program administrators.

- Delegation: The program gives beneficiaries dominant decision-making authority, and resolves disagreements between administrators and beneficiaries through a bargaining process.

- Community-led: Beneficiaries govern the philanthropic program and are fully in charge of administration. The program is essentially community-led with no intermediaries.

The three stages of a philanthropic program’s operation are informed by the Stanford Social Innovation Review article, “Listening to Those Who Matter Most, the Beneficiaries” by Fay Twersky, Phil Buchanan, and Valerie Threlfall, with context from Thomas Tufte and Paolo Mefalopulos‘s “Participatory Communication” guide. They include:

- Before: concerning initial research for and design of the program

- During: concerning program implementation

- After: concerning program evaluation and reform

By honestly assessing the level of participation at each stage of a program’s operation, organizations can begin to understand the risks they are undertaking in a concrete way.

See a full-size version of the rubric here

As an illustrative example, imagine that 10 small nonprofits from the Eastern Cape of South Africa form a community foundation with the aim of more-efficiently fundraising for their local operations. Each nonprofit shares equal representation on a committee responsible for allocating raised funds. Since the foundation was formed by its beneficiaries (the nonprofits), and the mechanism it uses for decision-making is controlled entirely by those beneficiaries, the first stage of the program (before) would get an eight rating (community-led). If the foundation’s participatory grantmaking mechanism works as planned with equal participation from each nonprofit, its second stage (during) would get a top rating as well. And if, at the end of the year, the nonprofits share impact assessments and other feedback related to their individual operations, and negotiate—giving equal weight to each other’s opinions—on how to improve the foundation’s governance, design, implementation, and even evaluation, it would earn its third perfect eight for the last stage (after).

On the other hand, consider a management consultant based in Washington, DC, who creates an education nonprofit to address shortcomings of public schools in South Africa’s Gauteng Province. After doing Internet research about South Africa’s public education system, he determines that low student test scores are a consequence of underqualified teachers in the community. He develops a new, video-based curriculum that students can watch from home on their cell phones, rather than attending a traditional school. The founder’s brief but successful fundraising campaign allows him to pay Gauteng-based consultants to collect input and feedback from students, and lobby for public schools to advertise his course. Since this program was conceived and designed without beneficiary input, the participation level during its first stage (before) might rate a three (informing). If, during the program’s second stage (during), it routinely gathers beneficiary input as intended—whether or not the founder elects to use that input—the program will earn a four (consultation). And if the program indeed collects and analyzes feedback from any served beneficiaries, then it may earn a four (consultation) for its final stage (after) as well.

These ratings help identify participation-related strengths and weaknesses—and, in turn, opportunity and risk. The community foundation, for example, has minimized the functional and ethical risks of nonparticipation, while the education nonprofit is significantly exposed to both. The nonprofit founder may find that most students cannot afford a device or access a stable Internet connection to take online courses. Moreover, the founder’s simplistic assessment of the cause of low test scores decreases the likelihood that his solution will address suitable points of leverage. And there is the ethical risk too: His lobbying of South African public schools to advertise his course lacks the democratic involvement of the community whose children he seeks to impact.

II. Considering Strategic Approach Types

The second part of the framework is about trying to understand the contextual factors that shape a philanthropic program’s three participation levels. Considering the various strategic approaches that a program takes to solving problems for its beneficiaries is one of the most important ways to do that. Understanding this can help illuminate why participation gaps exist and what structural obstacles the organization must surmount to fill them in.

There are many ways to segment approaches to philanthropy, but five common approaches include:

- Research: The organization produces technological, medical, or other expertise to develop and implement a philanthropic program. Examples include family planning and medical research organizations.

- Relief: The organization addresses the immediate needs of beneficiaries. Examples include disaster-relief and first-aid organizations.

- Small Scale: The organization specializes in addressing the needs of a small community of beneficiaries. Examples include community legal advice offices and pop-up schools.

- Large Scale: The organization addresses the needs of a broad, large community of beneficiaries. An example is an organization addressing health epidemics that affect large populations.

- Grantmaking: The organization supports nonprofits or individuals through grants. Examples include international funds addressing poverty and local funds for providing scholarships.

A philanthropic program may use one or more of these approaches and pursue each to varying degrees. For example, the community foundation described above took both small-scale and grantmaking approaches to philanthropic problem-solving because it only had 10 beneficiaries and was primarily focused on assisting them through grantmaking. The education nonprofit, on the other hand, took a larger-scale approach by attempting to address the entire public-school population of Gauteng.

Each philanthropic approach presents unique obstacles to and possibilities for increasing participation. How meaningfully participation can be embedded in a program, and what sort of friction a program will come up against in the attempt to increase participation will be different for a locally based community foundation than for an international education nonprofit. For example, the former has an easier time finding representative beneficiaries and can give them democratic control of funding decisions. The latter struggles to find representative beneficiaries who can influence program design and implementation from a population of school children (or their parents) that live in an entirely different country.

III. Considering Other Institutional and Beneficiary Factors

The third part of the framework involves examining other contextual factors that shape the nature of a program’s participation obstacles and opportunities, such as the systemic challenges posed by institutional isomorphism, professionalization, and the pressure to scale. We should consider how these considerations can encourage philanthropic programs to become more corporatist or less holistic to improve fundraising prospects, since well-funded organizations are often nonparticipatory, professionalization requires systems and credentials that privilege wealthier backgrounds, and growth is the mantra of our capitalistic economic order.

And of course, the unique characteristics of beneficiaries—such as their geographic distribution, whether they are individuals or organizations, and whether they are rich or poor—are central to understanding the nature of participation obstacles and opportunities as well. For example, philanthropic programs that address beneficiaries across a large rather than small geographical area may find it more difficult to involve those beneficiaries meaningfully in program decision-making. Moreover, it can be simpler for a program to address the needs of organizations rather than individuals, because the needs of organizations may be more readily apparent. Finally, richer rather than poorer beneficiaries are more likely to have higher levels of education and experience with navigating institutional processes, which might make it easier based on systemic pressures to include them in administrative components of philanthropic programs.

These contextual factors illuminate some of the challenges funders and administrators face in trying to make a program more participatory, and how funding and other pressures have shaped a program. Acknowledging them also makes it clear that we can work around and sometimes challenge certain factors. That’s important because every philanthropic program is capable of mitigating the risks of nonparticipation and increasing participation, no matter its distinct pressures.

Most rudimentarily, funders and administrators can use this framework to understand the degree of beneficiary participation in a philanthropic program, and by doing so, make sense of why and to what extent that program is exposed to the functional and ethical risks of nonparticipation. Risks are not guarantees of failure, and becoming aware of them should not automatically give rise to moral condemnation. But philanthropic organizations should work to mitigate them with all the passion moral enterprises muster, because in philanthropy, risk is existential—for intended beneficiaries especially. If this framework helps funders and administrators communicate how exposed a program is to the systemic risks of nonparticipation—especially in the service of providing an impetus to increase participation—it has done its job. Using it alongside the many other available tools may help push us a little closer to a meaningfully participatory world of philanthropy.

Return to Insights & Events